NATIVE ART PRESS

HYPERALLERGIC | APRIL 13 2025

The Artist Reviving a Native Hawaiian Clothmaking Tradition

By Isa Farfan

Lehuauakea, a Kanaka Maoli artist and practitioner of kapa, or Native Hawaiian bark clothmaking, felt called to reclaim the practice — which was nearly wiped out by the 1900s as the United States illegally annexed the territory — when they moved away from home to Oregon during high school.

Years later, Lehuauakea splits their time between Santa Fe, on “the continent,” and the Island of Hawaiʻi, where they grew up. Lehuauakea gathers, soaks, and beats tree bark, usually from the wauke or paper mulberry tree, to create kapa, which they dye with natural pigments to form large-scale installations, textiles, and experimental mixed-media works.

Last month, Lehuauakea became the second recipient of the Walker Youngbird Foundation’s twice-annual $15,000 grant for emerging Native American artists, which will also prepare them for a solo exhibition at the New York City gallery Nunu Fine Art in 2026.

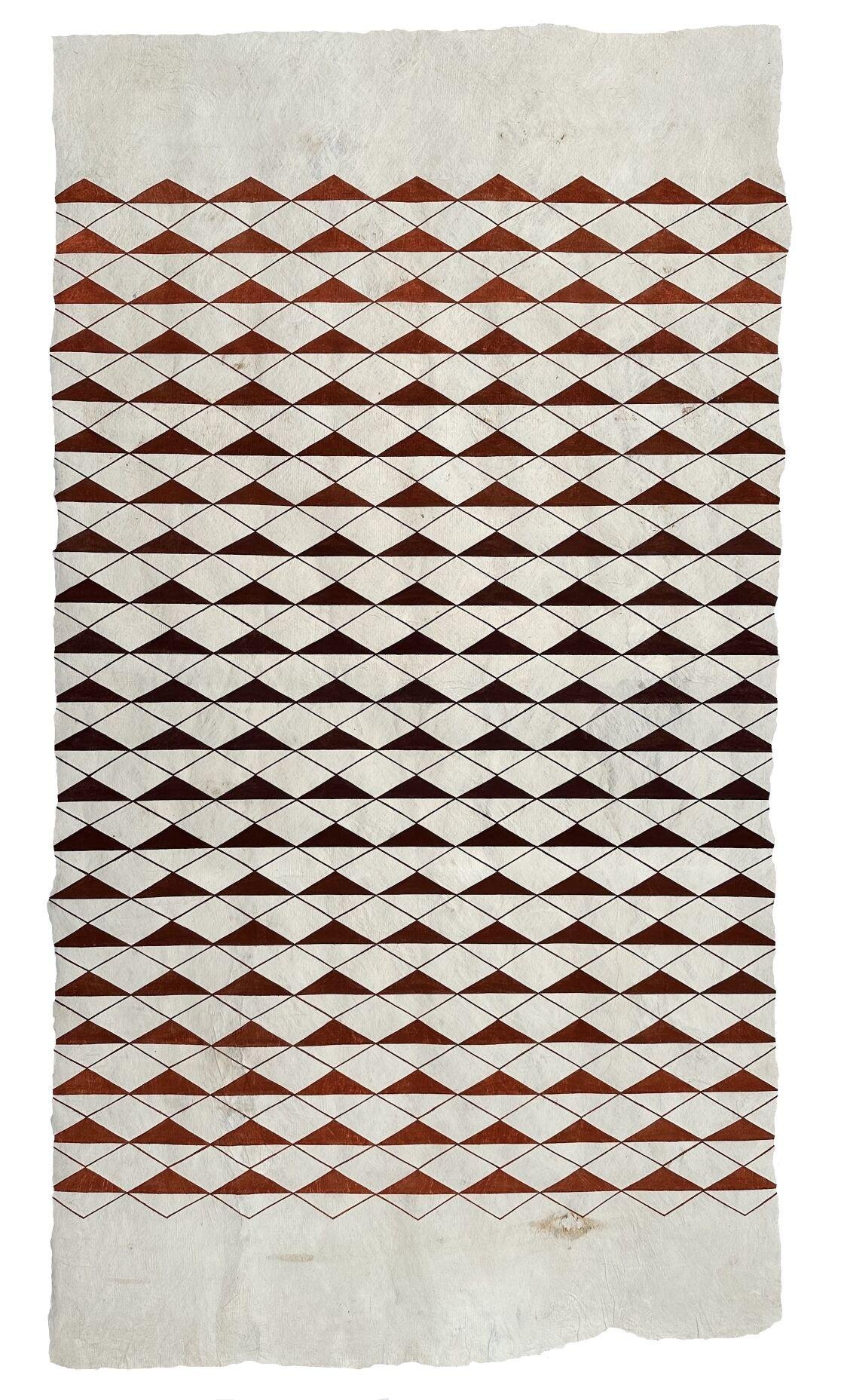

Lehuauakea, Lupe Hōkū (Star Kite), 2023

HYPERALLERGIC | APRIL 7 2025

Indigenous Art History Has Been Waiting for You to Catch Up

By Petala Ironcloud

“It’s a good day to be Indigenous,” Thomas Builds-the-Fire declares in the 1998 Native comedy, Smoke Signals — a fitting prelude to the staggering monument to Native resilience that is Indigenous Identities at the Zimmerli Art Museum, the late Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s final curatorial salvo. Rooted in a circular worldview in which humanity is inseparable from nature — in stark contrast to the linear, extractive logic of American colonialism — the exhibition is the most extensive display of Native American art to date, numbering 100 works by 97 artists. I was struck in particular by the haloed elk in Norman Akers’s “Drowning Elk” (2020), which drifts in a lake of crushed plastic bottles — a quiet martyr. I felt that I found a spectral stand-in for Quick-to-See Smith, the show’s late curator, who walked on just days before the opening. An artist and environmental activist, Smith’s passing feels like a final warning: a departure from a world too broken to be saved.

Wendy Red Star, Dust, 2020

ARTNEWS | MARCH 31 2025

15 Native American Women Artists to Know

By Petala Ironcloud

Native American artists, especially women, have only recently gained a spotlight within the mainstream art world. For centuries, Native art was siloed on reservations, at trading posts, and in Indian markets, with no dedicated Indigenous commercial galleries either in urban Indian centers like New York City, San Francisco, Tulsa, or Phoenix or in other areas with significant Native populations. But lately they are finding their way into major galleries and institutions from Miami to New York to Venice.

For Women’s History Month, we delve into art from 15 Native American, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian women. While not an exhaustive list, these artists represent a broad spectrum of artistic innovation spanning multiple generations and mediums, from foundational pottery to contemporary Ravenstail weaving. Shattering conventional ideas about fine art while honoring historical techniques and cultural knowledge, they underscore the vitality of Indigenous women’s contributions to contemporary art and the ongoing need to ensure that their voices and visions are centered in mainstream art discourse.

Dyani White Hawk, Visiting, 2024

ARTNEWS | MARCH 31 2025

15 Native American Women Artists to Know

By Petala Ironcloud

Native American artists, especially women, have only recently gained a spotlight within the mainstream art world. For centuries, Native art was siloed on reservations, at trading posts, and in Indian markets, with no dedicated Indigenous commercial galleries either in urban Indian centers like New York City, San Francisco, Tulsa, or Phoenix or in other areas with significant Native populations. But lately they are finding their way into major galleries and institutions from Miami to New York to Venice.

For Women’s History Month, we delve into art from 15 Native American, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian women. While not an exhaustive list, these artists represent a broad spectrum of artistic innovation spanning multiple generations and mediums, from foundational pottery to contemporary Ravenstail weaving. Shattering conventional ideas about fine art while honoring historical techniques and cultural knowledge, they underscore the vitality of Indigenous women’s contributions to contemporary art and the ongoing need to ensure that their voices and visions are centered in mainstream art discourse.

Dyani White Hawk, Visiting, 2024

HYPERALLERGIC | MARCH 24 2025

Woven Being Interweaves the Complexities of Native Art and Life

By Lori Waxman

The single greatest collage I have ever seen is by Frank Big Bear, a member of the White Earth Ojibwe tribe. “The Walker Collage, Multiverse #10” stretches more than 30 feet wide and includes cut-out images of everything. I mean everything: Cycladic figurines and Cindy Sherman dress-up, Assyrian kings and Marilyn Monroe, the human brain and a poison dart frog and high fashion and war death and family and friends and a Studio Gang high-rise and the cosmos. And that’s only about two dozen of the individual panels that comprise the tidy wall-length grid Big Bear completed in 2016. Any one of those is a good collage on its own, but there are 432 of them, each made on an identical invitation card for an exhibit by Star Wallowing Bull, the artist’s son. Most interconnect, mesmerizingly and surrealistically, and the sum total is utterly flabbergasting.

Big Bear is one of 33 artists including in Woven Being: Art for Zhegagoynak/Chicagoland, an ambitious if uneven exhibition currently on view at Northwestern University’s Block Museum.

HUFFPOST | MARCH 24 2025

This Native American Photographer Is Sparking An Important Conversation About Environmental Racism

By Kate Nelson

“I’ve been an environmental activist my entire life,” says Native American photographer Cara Romero, who recalls growing up in the ’80s on the Chemehuevi reservation in the Mojave Desert of California. There she watched the strong example set by female relatives such as her grandmother, who at the time, was the chairwoman of their tribe.

“I was raised in a very pristine environment with an intact, undisturbed ecosystem and lots of flora and fauna,” Romero says. “I watched the world around us become very developed, and witnessing that level of encroachment happen within my lifetime made me want to be a protector of what we still have. As Native people, we’re really the guardians of the land and water.”

Though Romero has plenty of advocacy experience under her belt, her primary medium for affecting change is fine art photography — she’s had exhibits, over the past decade, at both the The Met and the Museum of Modern Art. Much of her otherworldly imagery examines the intersection of Indigenous tradition and environmental development in an evocative yet nuanced way that leaves a lasting impression on its viewers.

Cara Romero, Miztla, 2021

ARTNET | MARCH 12 2025

Which Artists Are Getting the Most Play in U.S. Museums This Month?

By Ben Davis

I am back with our quarterly look at which artists are having a moment at art institutions in the United States.

Three of the six artists here have Native American backgrounds. Their names in some cases overlap in the large number of current shows devoted to celebrating Indigenous artists at U.S. museums right now.

The Santa Fe-based Romero, Cara Romero, (b. 1977) is a maker of vivid, stylized photos. She has staged dream-like imagery evoking the history of Native displacement (Water Memory, 2015), made work mocking the depictions of Native Americans in pop culture (TV Indians, 2017), and most recently explored a stylish “Indigenous Futurism” (3 Sisters, 2022). “My greater intention is to create a critical visibility for modern Natives, to get away from that one-story narrative, and to dig into our multiple identities,” she told New Mexico Magazine back in 2019.

This month, the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., is featuring a large retrospective of her work, including pieces she did with students styling them as life-size “American Doll” figures. Meanwhile, the Figge Museum in Davenport, Iowa, has an exhibition pairing her photography with the work of her husband, Diego Romero, who fuses Pueblo pottery tradition with comicbook-style graphics to witty effect.

Student Kaitlyn Anderson poses in a doll-box set with Native Hawaiian props for photographer Cara Romero

ARTNET | MARCH 12 2025

Desert X Descends on Coachella Valley. Here Are 5 Awe-Inspiring Works

By Jo Lawson-Tancred

There is no museum that could contain art made on a truly monumental scale. It needs space to breathe. In turn, man-made architectural and artistic interventions have an almost paradoxical ability to articulate a landscape of already stunning natural beauty. It is these elements that make Desert X a much-anticipated staple of the art world calendar that always promises panoramas verging on the sublime. The 2025 edition is no different.

The seemingly endless stretch of desert in Coachella Valley is usually admired while on the move, and Cannupa Hanska Luger’s unusual vehicle for G.H.O.S.T Ride (Generative Habitation Operating System Technology) will be making some pitstops over the course of Desert X’s run. The artist lives in New Mexico but was born on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota. His shiny caravan’s wacky collection of accoutrements may even be capable of time travel, as it channels imagined, speculative futures that center the region’s Indigenous communities.

Installation view of Cannupa Hanska Luger, G.H.O.S.T. Ride (Generative Habitation Operating System Technology) at Desert X 2025

SEE GREAT ART | MARCH 8 2025

Contemporary Native American artists vs. 19th century landscape painting

By Chadd Scott

The Farnsworth Art Museum (Rockland, ME) presents Native Prospects: Indigeneity and Landscape, a traveling exhibition from the Thomas Cole National Historic Site (Catskill, NY). Curated by Scott Manning Stevens, Karoniaktatsie (Akwesasne Mohawk), Native Prospects invites visitors to explore the complex relationship between Indigenous cultures and the landscape through a unique juxtaposition of contemporary Native American art and Indigenous works of historic and cultural value and 19th-century American landscape paintings, including works by Thomas Cole. Native Prospects also marks a remarkable moment in art history with the return of Cole to Maine, and will be on view from March 8 through July 6, 2025.

Kay WalkingStick, Niagara, 2022

BOMB MAGAZINE | MARCH 3 2025

Jordan Ann Craig by Caitlin Lorraine Johnson

I walk through the door to Jordan Ann Craig’s studio in Pojoaque, New Mexico, which she’s only moved into a few days before, so the front room is minimally furnished but immaculate—warm white walls, exposed wooden beams, a skylight. Bottles of Golden acrylic paint neatly line a wall of seven shelves. Jordan lifts her hand to a green bruise and explains that she hit her forehead on a bracket while installing these shelves last night. As we walk around the room, I think about how difficult it is to strip anything bare and then make it your own. Whenever I see a painter face a blank canvas, the next step feels impossible.

Jordan Ann Craig, Sharp Tongue Used to Cut Deep, 2024

ARTFORUM | MARCH 1 2025

The Checklist: Jordan Poorman Crocker

In 2023, Jordan Poorman Cocker (Kiowa Tribe and Kingdom of Tonga) was appointed the first full-time curator of Indigenous Art at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas. Her exhibition “American Sunrise: Indigenous Art at Crystal Bridges,” a survey of over thirty artists spanning 150 years, is on view through March 23. While many art museums inscribe Indigenous nations within colonial frameworks (with their histories beginning and ending with colonization), Poorman Cocker’s curatorial work emphasizes their contemporaneity and continuity. She is also a traditional Kiowa beadwork and textile artist, operating her own atelier, MÀYÍ, since 2018.

Photo by Ryan RedCorn

COWBOYS & INDIANS MAGAZINE | FEBRUARY 20 2025

Meet the Indigenous Designers Behind Our Dark Winds Cover

By Kate Nelson

Here in their own words, the Indigenous creators describe their designs, their inspirations, and their aspirations for the year ahead.

For our exclusive cover story shoot, we tapped four Native American fashion and jewelry designers to dress the stars of the AMC crime thriller Dark Winds, which films just outside Santa Fe at the Indigenous-owned Camel Rock Studios. It seemed only fitting to feature a quartet of Southwest-based creatives, whose work reflects not only their unique worldviews but also the stunning natural landscape that surrounds them.

Photography by Cara Romero

EXPERIENCE SCOTTSDALE | FEBRUARY 2025

Diné Artist to Curate Exhibition at Scottsdale Ferrari Art Week

Scottsdale Ferrari Art Week Fair is pleased to announce that Diné artist, dealer, curator and Antiques Roadshow Appraiser, Tony Abeyta, will curate a special exhibition, "Desert Modernism," which will show the convergence and progression of Phoenix artists of Native, Anglo and Hispanic descent, from approximately 1930-1980.

The exhibition will feature rare and hard-to-find works by artists, architects and designers such as Fritz Scholder, Charles Loloma, Lloyd Kiva New, Frank Lloyd Wright, Phillip Curtis and Paolo Soleri. Abeyta is also serving as an Advisory Committee member for the Fair.

The Scottsdale Ferrari Art Week Fair is a unique event at the historical and cultural crossroads of the American Southwest. Set in one of the country’s fastest-growing cities with an ascendent contemporary Indigenous culture, the fair will showcase over a hundred leading international galleries at Westworld, March 20-23, 2025.

“We are absolutely thrilled to have Tony participate in Scottsdale Art Week,” says Trey Brennen, co-owner of the inaugural Fair.

Preston Singletary, A Canoe Entered a Dream

INDIAN COUNTRY TODAY | FEBRUARY 14 2025

INDIGENOUS A&E: Land spirit art, clan house redux, fur flies at fashion shows

By Sandra Hale Schulman

Land continues to be the story – really the only story – in life, politics and art. With the devastating fires in Los Angeles, James Trotta-Bono of Trotta-Bono Contemporary gallery is using his space as a vehicle to combine his decades-long art background with a passion for contemporary Native art. He has curated many shows in Santa Fe during Indian Market.

His upcoming exhibition, Spirit of Place: Exploring Our Relationship to the Land will open February 22 with artists Kent Monkman, Richard Glazer Danay, Cara Romero, Yatika Starr Fields, Emmi Whitehorse, David Bradley, Margarete Bagshaw, the late Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and Fritz Scholder. A portion of proceeds will be donated to local wildfire relief efforts.

In a news release, he said, “Indigenous communities have been stewards of the land since time immemorial. The artists in this exhibit expand upon that legacy. They have articulated their unique talents to highlight both connection and disruption. This timely body of work provides context for reflection, dialogue and action.”

Kent Monkman, Protecting the Medicines, 2023

LAKOTA TIMES | FEBRUARY 12 2025

Oscar Howe First Catalogue Raisonné

The University of South Dakota Art Galleries has assembled a team of scholars, researchers and assistants to establish a catalogue raisonné — the complete works of Oscar Howe, artist in-residence and professor of art at USD.

“I am pleased and honored to assist the University of South Dakota and its select team of curators, artists and art historians in this massive project that compiles and publishes a comprehensive volume detailing the many unique works of my father,” said Inge Dawn Howe Maresh, Howe’s daughter.

This project honors his work and legacy. The full catalogue will be digitally accessible by December 2026. The USD Art Galleries is excited to enter the second phase of the Howe database project, connecting with private collectors who are a vital part of Howe’s legacy and the preservation of his artwork.

FRIEZE | FEBRUARY 10 2025

Native American Artists Claim Space at Frieze Los Angeles

By Tara Anne Dalbow

In 2024, Mississippi Choctaw-Cherokee painter, sculptor and filmmaker Jeffrey Gibson made history by becoming the first Native American artist to represent the US at the Venice Biennale. His Technicolor pavilion, comprising intricately beaded sculptures, geometric paintings and a kaleidoscopic video installation, was inaugurated by Native American dancers and singers performing the traditional jingle dress dance – another first. Indeed, Adriano Pedrosa’s ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ biennial featured more Indigenous artists than any previous edition. Among them were fellow Native Americans, Navajo painter and printmaker Emmi Whitehorse and Cherokee painter Kay WalkingStick, whose work is also being showcased on the US West Coast for the first time in 40 years at Frieze Los Angeles 2025.

Kay WalkingStick, Memory of the Santee Sioux, 1978

FORBES | JANUARY 29 2025

Zimmerli Art Museum Opening Exhibition Of Contemporary Native American Art Curated By Recently Deceased Jaune Quick-To-See Smith

By Chadd Scott

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (1940-2025; Citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation) passed away on Friday, January 24, 2025, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. She had been a driving force in contemporary Native American art since the mid-70s making work, organizing shows, uplifting other artists, networking, and constantly advocating for the genre on panels.

Through the decades, she collected people to her circle the way museums now collect her paintings. For Smith’s largest curatorial project, completed prior to her death, a massive exhibition opening at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, NJ on February 1, 2025, she didn’t go any further than the contacts in her phone to fill out the roster of 97 artists.

“We know everybody in the show,” Smith’s son Neal Ambrose-Smith, who assisted on the effort, told Forbes.com in an interview conducted prior to his mother’s passing. “Not all of them have been to our house and had dinner, but a lot of them have. That's just part of our community.”

Zoë Urness, 'Year of the Women,' 2019

VOGUE | JANUARY 29 2025

Remembering Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a Native Artist Who Changed the Way We Saw America

By Christian Allaire

The art world has lost a trailblazer.

On Tuesday, Indigenous artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith—whose raw works depicting contemporary Native life have appeared at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Denver Art Museum, and other major institutions—died at 85, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. The news was confirmed by the Garth Greenan Gallery in New York.

Smith, who was of Salish-Kootenai, Métis-Cree, and Shoshone-Bannock descent, enjoyed a fruitful career as a painter, mounting more than 80 solo exhibitions—including the 2023 retrospective “Memory Map,” held at the Whitney in New York—over five decades.

She was born in 1940 on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana, where she was raised by her father, a horse trader. In the late 1970s, after studying at Olympic College in Bremerton, Washington, and the University of New Mexico, Smith began to develop the style that became her signature, rooted in abstract landscapes, Jasper Johns-esque maps, and pictographs addressing some of the issues facing modern Native Americans.

Photograph by Thomas King

FORBES | JANUARY 16 2025

Cara Romero’s First Major Solo Museum Show Opening At Hood Museum Of Art

By Chadd Scott

When Cara Romero (b. 1977) found herself unable to adequately communicate in words her indigenous experience in America, she turned to another language: photography.

Romero split her childhood between the sprawling metropolis of Houston and the remote Chemehuevi reservation in Mojave Desert, CA. As an undergraduate anthropology student at the University of Houston, she couldn’t fully express what she saw, felt, and experienced on the reservation.

During her junior year, she stumbled into a black and white film class.

“While I struggled writing about contemporary Native issues, I fell in love with (photography) for its power of storytelling,” Romero told Forbes.com. “I loved the mad science of it. It made my heart sing, and I never wanted to quit. There was always what I call a healthy compulsion. I wanted to get better. I wanted to do it in my spare time. I never imagined in million years that it would take me so far.”

All the way to her first major solo museum exhibition at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College. “Cara Romero: Panûpünüwügai (Living Light)” will be on view from January 18 through August 10, 2025, at the Ivy League school in Hanover, NH.

Cara Romero, Water Memory, 2015

OBSERVER | JANUARY 7 2025

For Nicholas Galanin, Art Is a Tool of Indigenous Resilience and Resistance

By Elisa Carollo

Amid growing interest in and recognition of contemporary Indigenous practices, Nicholas Galanin, a Tlingit-Unangax̂ artist and member of the Sitka Tribe of Alaska, has made his name in the contemporary art scene with an original multimedia practice entirely dedicated to reclaiming and championing Indigenous narratives. His work envisions a future in which culture, land, and identity are protected and celebrated.

During Art Basel Miami Beach, the artist hit the headlines again, not with the flashy artwork we might expect in that context but instead with another highly provocative site-specific public work, Seletega (run, see if people are coming/corre a ver si viene gente) installed at the Faena Hotel. There, 45-foot tall white sails towered over the luxurious beachfront, just as a 15th-century galleon had been buried under the sand and was now emerging with its heavy history of colonization embedded within. “At the time of initial contact for a lot of our communities, those sails were the first things we saw on the horizon,” Galanin told Observer a week after the installation’s debut. “The work speaks toward the collective liberation of humanity. It speaks towards capitalism at the core of some of the colonial violence that communities are faced with.”

Nicholas Galanin, Seletega, 2024

COWBOYS AND INDIANS MAGAZINE | JANUARY 6 2024

Native Art Checks Into the New Thompson Hotel

By Sandra Hale Schulman

Located in downtown Palm Springs on Agua Caliente tribal land, the luxe new Thompson Hotel features museum-quality American Indian art.

Native American tribes have lived in the Coachella Valley since time immemorial — the sheltering mountains and bubbling hot springs made for abundant living.

For modern visitors, the attraction of downtown Palm Springs lies in the unique combination of the city’s rich Indigenous cultural heritage with modern design. The newest hotel in the heart of downtown marries these elements in a grand style.

The Thompson Palm Springs spans two and a half city blocks and features a stunning collection of contemporary Native American art by artists whose works can be found in museums worldwide.

Jeffrey Gibson’s mural The Land Is Speaking Are You Listening

COLOSSAL MAGAZINE | DECEMBER 24 2024

Nicholas Galanin Hews Visions of the Present From Indigenous Knowledge, Land, and Memory

By Kate Mothes

For Tlingit-Unangax̂ artist Nicholas Galanin, looking to the past is fundamental to constructing a more nuanced perception of the present. His multidisciplinary practice “aims to redress the widespread misappropriation of Indigenous visual culture, the impact of colonialism, as well as collective amnesia,” says a statement from Peter Blum Gallery, which represents the artist and is currently showing Galanin’s solo exhibition, The persistence of Land claims in a climate of change.

“We can sharpen our vision of the present with cultural knowledge and memory,” Galanin says. “These works embody cultural memory and practice, reflecting persistence, sacrifice, violence, refusal, endurance, and resistance.”

Nicholas Galanin, Never Forget, 2021

ARTNEWS | DECEMBER 18 2024

Year In Review: 2024 Saw a New Level of Interest in Indigenous Art—the Market Response Has Been More Complicated

By Karen K. Ho

In January, several industry insiders predicted there would be more attention paid this year to Indigenous and Native art. That month, Phillips was gearing up to hold “New Terrains,” its first selling exhibition of contemporary Indigenous and Native art at its New York headquarters. Quickly, it became apparent that the predictions made around the time of the Phillips show were correct. Later that month, the Venice Biennale would announce its artist list for the main exhibition, “Foreigners Everywhere,” which included numerous Indigenous artists.

Now, 2024 is nearly complete, and further proof that Indigenous art is on the rise has arrived in museums, auction houses, and galleries. Jeffrey Gibson (Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians/Cherokee), the artist who represented the United States at the Venice Biennale, got representation with Hauser & Wirth. Emmi Whitehorse, a Diné painter who showed in the Biennale’s main exhibition, gained a new auction record at Phillips, where one of her paintings sold for over $177,000—nearly nine times its high estimate. A retrospective for Aboriginal painter Emily Kam Kngwarray continued to travel Australia, and even resulted in the late artist’s addition to Pace’s roster.

Emmi Whitehorse (Diné), Canyon Lake I, 2001

ARTNEWS | DECEMBER 16 2024

The Defining Art Events of 2024

Native and Indigenous art continued to be featured in museum exhibitions and in the market, boosted by the visibility of Jeffrey Gibson (Choctaw/Cherokee) representing the US at the Venice Biennale this year. Both of the Biennale’s top prizes also went to Indigenous artists, and the façade of the central exhibition hall was covered with a mural by an indigenous collective from the Brazilian Amazon.

Phillips held its first exhibition sale focused on Native and Indigenous art in January. Then, in May, the auction house set a new artist record for Kent Monkman (Cree) after his 2020 painting The Storm sold for $300,000 ($381,000 with fees).

Solo shows for Native and Indigenous artists this year included Dyani White Hawk (Sičáŋǧu Lakota) and Nicholas Galanin (Tlingít/Unangax̂) at the Baltimore Museum of Art; Mary Sully (Yankton Dakota) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; and Melissa Cody (Navajo) at MoMA PS1. The Cincinnati Art Museum also held a large exhibition of glass works by contemporary Native American and Indigenous Pacific-Rim artists, while the Blanton Museum of Art currently has an exhibition curated by Wendy Red Star (Apsáalooke).

There are already signs the momentum will continue into 2025: The Denver Art Museum announced that next year it will hold a large-scale exhibition of works by Monkman, the first museum survey for Andrea Carlson (Ojibwe), and a partial reinstallation of its collection of Indigenous art. The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art, will also open at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., next October before traveling to other venues in Canada and the US.

Jeffrey Gibson at the Venice Biennale

ARTDAILY | DECEMBER 12 2024

Works by contemporary Native American artists acquired by the National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of Art has acquired paintings, sculptures, a video, and several photographs by contemporary Native American artists Jeffrey Gibson, Sky Hopinka, Cannupa Hanska Luger, Dakota Mace, Eric-Paul Riege, Cara Romero, Kay WalkingStick, and Will Wilson, reinforcing its ongoing commitment to acquire major works that expand perspectives of the history of art, especially in the United States. Offering a critical perspective in contemporary artistic discourse and presenting a reflection on the history of the native lands and cultures of Indigenous artists, these acquisitions complement works already in the collection by G. Peter Jemison (Seneca Nation of Indians, Heron Clan), George Morrison (Ojibwe [Grand Portage]), Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes), Marie Watt (Seneca Nation of Indians), and Emmi Whitehorse (Diné), among others, and build on the dialogues forged in the exhibition The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans, presented by the National Gallery from September 22, 2023, through January 15, 2024.

Jeffrey Gibson, WE HOLD THESE TRUTHS TO BE SELF-EVIDENT, 2024

ARTNET | DECEMBER 9 2024

Which 6 Artists Dominate U.S. Museums Right Now? We Crunch the Numbers

By Ben Davis

I looked at more than 200 museums, and counted which artists were on view any time during December (that includes a show like the Baltimore Museum’s “Illustrating Agency,” which closed December 1). The resulting list includes a little more than 3,400 artist names. Of these, only about 300 appear more than once—a tiny fraction. And of these, a very few repeat multiple times, giving a sense of which voices are most resonating with curators and institutions.

Because I’m most interested in breadth of influence, I decided not to make any distinctions between bigger and smaller institutions. I rank career retrospectives and surveys highly, followed by special commissions or exhibitions that spotlight a specific body of work, biennial appearances, and then inclusions in thematic group shows.

All the most visible figures are Black and Indigenous. A rhetoric of speaking for and to historically marginalized identities surrounds a lot of the work.

Virgil Ortiz

HYPERALLERGIC | NOVEMBER 26 2024

Weaving Through the History of Diné Textiles

By Nancy Zastudil

I’m standing in a low-lit gallery, looking into a floor-to-ceiling glass case displaying three textiles: one, a horizontal field of black and white parallelograms; another, a spread of vertical brown, red, and beige zigzagging lines that form a scalloped edge on either side; the third composed of wide horizontal bands of vertical zigzags, this time black and beige, along with narrower red bands punctuated by a series of diamond shapes outlined in black. The visual vibrations and patterns feel completely of the earth and the human hand. Each of these works — one tapestry and two blankets — appears timeless, but in fact they were created in two different centuries.

The works are part of Horizons: Weaving Between the Lines with Diné Textiles at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (MIAC). To organize the exhibition of over 30 textiles, photographs, and related items (e.g., dye samples, yarn swatches, digital media), co-curators Hadley Jensen and Rapheal Begay (Diné) collaborated with a Diné advisory committee; a similar approach was used for Grounded in Clay at the MIAC last year.

Darby Raymond-Overstreet, Woven Landscape: Monument Valley, 2023

HYPERALLERGIC | OCTOBER 23 2024

From the Ruins of the Past, Indigenous Artists Fashion New Futures

By Joelle E. Mendoza

“Maybe ‘apocalypse’ is the opportunity we are looking for, even if we don’t quite know it yet.” This message from Santa Clara Pueblo sculptor Rose B. Simpson is printed at the feet of her over-eight-foot-tall figurative sculpture “Ground (Witness)” (2016) at the Autry Museum of the American West. The artist’s evocative “maybe” can provide a generative perspective in this political moment, as many Indigenous communities continue to survive the apocalyptic reality of European settler colonialism.

Future Imaginaries: Indigenous Art, Fashion, Technology, in which Simpson’s towering sculpture is situated, was organized by the Autry Museum as part of the Getty Foundation’s PST ART: Art & Science Collide program and runs through June 21, 2026. With over 50 pieces on view, the show aims to challenge specific preconceived notions of what constitutes Native art through the work of contemporary Indigenous artists who explore ideas of time, technology, futurism, and science. It includes a range of tribal representation and multidisciplinary approaches that draw from ancestral knowledge and technology, interrogating how future generations might preserve and adapt traditions to carry them forward.

Wendy Red Star, Stirs Up the Dust, 2011

HYPERALLERGIC | OCTOBER 13 2024

Native Art Collection Gets a Much-Needed Rehang at Montclair Art Museum

By Greta Rainbow

A decade ago, Anishinaabe scholar Grace Dillon coined the term “Indigenous futurisms.” The phrase is not a call to ignore a painful past, she wrote, but rather to fold the past into the present. When this past-present meets the future, it creates “a philosophical wormhole that renders the very definitions of time and space fluid in the imagination.”

Historically, Indigenous art has been clumsily slotted into the Western canon. Museums tend to conceive of Native identity as static or even a thing of the past, relegating ephemera to the furthest, darkest corner of its permanent collections. In the long-term installation Interwoven Power: Native Knowledge / Native Art, which opened on September 14, New Jersey’s Montclair Art Museum (MAM) achieves a sorely needed curatorial feat: an institutional display of Indigenous art that courses with vitality.

OBSERVER | OCTOBER 11 2024

How Denver Art Museum Is Looping Indigenous Communities into Its Program

By Elisa Carollo

The Denver Art Museum was among the first institutions in the U.S. to collect Native American art, beginning in 1925, and has maintained a steadfast commitment to highlighting the contributions of Indigenous artists. “The impact of Indigenous people on the collection is fundamental,” Heinrich said in his speech, “It has always been essential for us to collect contemporary art by Native American people.”

This month, the museum is celebrating the 100th anniversary of its Indigenous Arts of North America collection with a complete rehanging of its Indigenous works. “As we approach the 100th anniversary of the DAM’s Indigenous Arts of North America collection, we take this moment to honor and uplift Native voices and perspectives by communicating the many contributions Indigenous artists, advisors, and scholars have made to our museum,” Dakota Hoska, associate curator of Native Arts, told Observer. “We are excited to expose our larger audiences to the beauty and innovation found in Native North American artwork throughout time.”

Kent Monkman, Compositional Study for The Sparrow, 2022

HARPER’S BAZAAR | OCTOBER 4 2024

Wendy Red Star Is Decolonizing the Art World With Humor—and Help From Her Ancestors

By Ariana Marsh

Red Star’s artmaking practice has always served as a dialogue between past and present. Best known for her photography work confronting stereotypes about Native American identity, she also works in sculpture, installation, performance, and fashion to correct harmful historical narratives and act as a cultural archivist for the Crow community. Represented by Sargent’s Daughters in New York, Red Star also recently joined Roberts Projects gallery in L.A., where she had her first solo exhibition, “Bíikkua (The Hide Scraper),” earlier this year. Now, the 2024 MacArthur Fellow is gearing up for her biggest solo show to date: an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., in 2026, which will focus on Plenty Coups, the last chief of the Crow to be elected by other chiefs. “I'm on this exciting adventure of research right now,” Red Star says of the project. “There’s so much to Plenty Coups’s legacy and history—we’ve found mentions of him across all the Smithsonian institutions.”

How Raven Halfmoon Channels Indigenous History and Identity Into Her Monumental Sculptures

ARTNET | SEPTEMBER 23 2024

By Katie White

Raven Halfmoon (Caddo Nation) makes monumental, totemic sculptures that speak to the living power of indigenous peoples. Halfmoon is best known for towering, glazed stoneware figures that loom at more than twice a human scale and can weigh hundreds of pounds. These figurative beings, whom Halfmoon builds from a coil method, bridge Caddo pottery traditions with ideas rooted in the artist’s feminist matrilineal ancestry along as well as a range of artistic influences including Land Art and the Moai figures on Rapa Nui (Easter Island).

Now in a new exhibition “Neesh + Soku (Moon + Sun)” at Salon 94 in New York, the artist has taken inspiration from her name —Halfmoon—to mine the binaries of light and dark, male and female, past and present, while finding meaning in the rich spaces in between. Here for the first time, the artist presents work in stone and bronze, in addition to new stoneware sculptures. In these works, twinned figures appear, hinting at the multiplicities present in each person. Her works are still monumental, and include a 9-foot bronze sculpture and a 7-foot figure made from travertine.

BOSTON.COM | SEPTEMBER 19 2024

New Dewey Square mural honors Indigenous heritage

By Nia Harmon

In partnership with the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), The Greenway Conservancy will feature its first mural designed by an Indigenous artist with its 10th installation in the cycle.

Indigenous-American multidisciplinary artist Jeffrey Gibson will debut your spirit whispering in my ear on Sept. 19 with an opening celebration that includes performance, art-making, and music from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m.

The mural contains ten different elements that honor how Indigenous, Native, and other oppressed communities combat systemic obstacles “with faith, courage and strength,” Gibson said in a statement about the installation.

THE ART NEWSPAPER | SEPTEMBER 17 2024

Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore wins the Audain Prize, one of Canada’s top art awards

By Hadani Ditmars

The winner of the 2024 Audain Prize for the Visual Arts was announced Tuesday in Vancouver, recognising the distinguished Canadian artist Rebecca Belmore with a cash prize of C$100,000 ($73,500). A member of the Lac Seul First Nation (Anishinaabe) based in Vancouver and Toronto, Belmore is a multidisciplinary artist recognised internationally for her performance art, photo-based work and site-specific sculptural installations.

Rooted in the political and social realities of Indigenous communities, for decades Belmore’s art has made evocative connections between bodies, land and language. In 2023 for example, she was commissioned by the Polygon Gallery, in collaboration with the Burrard Arts Foundation, to create a large-format public work in North Vancouver. The commission, Hacer Memoria (2023), presented a series of blue and orange shirts made of tarpaulin, referencing the resilience of residential school survivors and offering an opportunity for the public to acknowledge Indigenous people.

Rebecca Belmore's ishkode (fire) 2022)

ARTSY | SEPTEMBER 17 2024

Jeffrey Gibson launches public art series in New York during Climate Week

By Maxwell Rabb

Jeffrey Gibson, the artist currently representing the United States at the 60th Venice Biennale, is presenting a series of public art installations during Climate Week New York. The project, running until September 29th, aims to spark public dialogue on climate change and the intricate relationship between humans and nature through immersive art experiences.

Central to the project is Gibson’s moving image animation, The Spirits Are Laughing (2024). This 11-minute video work, featuring animated designs and evocative texts, draws on Gibson’s Choctaw and Cherokee heritage to explore Indigenous kinship and environmental consciousness. The piece was originally created for The Hudson Eye art festival in 2021 and has been adapted for large-scale projections at several New York landmarks, such as Union Square, the Brooklyn Bridge, and Columbus Circle.

Jeffrey Gibson, still images from The Spirits Are Laughing, 2024

HYPERALLERGIC | SEPTEMBER 15 2024

Rachel Martin Serves Up a Communal Meal of Art

By Lakshmi Rivera Amin

A simple change of perspective can crack open a universe of possibilities — and in Rachel Martin’s galaxy, the artwork greets you upside down.

Her body arched in a backbend, a female figure donning a Tlingít mask perches on red-nailed fingers in an extraordinary balancing act, playfully beckoning visitors into the artist’s first solo show in New York City.

True to its name, Bending the Rules gathers 15 works on paper that defy convention in more ways than one. I felt a magnetic pull toward the Queens-based Tlingít artist’s imaginative field of vision, drawing from Indigenous Northwest Coast formline practices to conjure her own artistic vocabulary. Martin grew up between California and Montana’s Fort Peck Indian Reservation and connected with Tlingít culture later in life, most recently through learning to speak the language. Here, her capacity to weave cultural traditions together and imbue them with her distinctive voice has translated into inventive drawings that center the joy of communing, confiding, and sharing meals.

Rachel Martin, Bending the Rules, 2024

THE ART NEWSPAPER | SEPTEMBER 11 2024

Wendy Red Star brings contemporary Native American art to London

By Aimee Dawson

Since early June, walking into the London gallery Gathering has meant entering a colourful, 3D panorama of mountaintops, forest glades and a winding river reminiscent of a stage set for a primary school play. But the installation is not a vacuous vision of pastoral escape; it is a new work by the Apsáalooke (Crow) artist Wendy Red Star that ruminates on the colonisation of Native American land.

Her exhibition, In the Shadow of the Paper Mountains (until 14 September), takes its name from this new sculptural work. Made of painted fibreboard, the installation “intends to capture the reductive design language of the cheap greeting card and apply it to the Montana Crow Reservation landscape”, a press statement reads. The artist has added an audio recording from the Pryor Mountains—a sacred site of Apsáalooke history and folklore—that layers birdsong atop the sounds of insects and running water. These elements combine to raise a niggling question: How much of the complex truth of this place and its culture are being flattened in these generic images?

installation view, In the Shadow of the Paper Mountains, 2024

FORBES | SEPTEMBER 9 2024

Joslyn Art Museum In Omaha Does More Than Open New Building

By Chadd Scott

The Joslyn Art Museum has done it. Completely integrating Native American art into its broader American and contemporary galleries.

Plains beadwork work side-by-side with Mary Cassatt and Childe Hassam paintings in the American gallery. Thomas Hart Benton and the Kiowa Six as neighbors. Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Dakhóta) and Grant Wood. The Omaha museum’s contemporary galleries place Tom Jones (Ho-Chunk) with Mickalene Thomas, and Jeffrey Gibson (Choctaw) with Simone Leigh. A signature alcove given to Wendy Red Star (Apsáalooke).

American art museums have been making progress towards mainstreaming Indigenous art into their permanent collection display areas for a handful of years now–it’s a recent development–the Joslyn goes all the way. No silos. No ghettoization. No this here, that there. One in the same. Native American art indistinguishable from American art.

ALBUQUERQUE JOURNAL | AUGUST 25 2024

Can Santa Fe’s Indian Market Free Itself From the Settler Gaze?

By Sháńdíín Brown and Zach Feuer

What does it mean to be a real Indian artist who makes real Indian art? And what happens when they try to sell it?

James Luna (Payómkawichum, Ipai, and Mexican) approached the former question in his 1991 installation titled “Take a Picture with a Real Indian.” The artist invited visitors to take a picture with him or with three cut-outs of his likeness: one donning war dance regalia, another in a black t-shirt and slacks, and a third in a leather loincloth and moccasins. Settler viewers may understand only one layer of irony — the absurd idea that an “authentic” Native person exists as an artifact to be put on display. As they pat themselves on the back for being in on the joke, they replicate the same mechanism the work exposes: gawking at a Native person on display.

The latter question was on our minds over the weekend of August 17 at the Southwest Association for Indian Arts’s (SWAIA) annual Indian Market in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Work by Ken Williams Jr. (Arapaho/Seneca) at Shiprock Gallery

ALBUQUERQUE JOURNAL | AUGUST 25 2024

Quenching a thirst: Cara Romero Gallery exhibit celebrates the art of water

By Kathaleen Roberts

When photographer Cara Romero (Chemehuevi) first opened the only female Indigenous-owned gallery in Santa Fe in 2022, she intended to show only her own work.

But the success of the gallery at 333 Montezuma Ave. inspired her to expand her single artist stable to other Native creators she admired.

The exhibition “Slow Water” features more than 20 works by Indigenous artists Leah Mata Fragua, Porfirio Gutierrez, Ian Kuali’i, Lehuauakea, Erica Lord, Diego Romero and Cara Romero. The multidisciplinary works feature handmade kapa (barkcloth), textiles, jewelry, photography, ceramics, cut paper and more. The show runs through Oct. 2.

Lehuauakea, Kūmauna, 2024

FORBES | AUGUST 22 2024

SWAIA Indian Market: A One-Of-A-Kind Artistic Destination For 102 Years

By Chadd Scott

Bigger isn't better. Older isn't better. Friendly is better, but what most distinguishes the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts Indian Market each August in Santa Fe, NM is the caliber of the art. Better makes it better.

The jewelry here makes anything found on 5th Avenue in New York look “eh.” It would be laughable to compare contemporary pottery anywhere else in the world to that seen at Market. The silverwork is otherworldly. The painting, sculpture, and photography comparable to the world’s best fairs.

What's on view and for sale at Santa Fe Indian Market is the best of the best contemporary art. Indigenous made, yes, but contemporary art writ large.

Pursuing the artist booths alongside collectors are museum curators looking to bring home treasures. Direct from the maker.

VOGUE | AUGUST 20 2024

Style Was Embedded With Culture at the 2024 Santa Fe Indian Market

By Christian Allaire

Early Saturday morning, just as the sun was rising and the 2024 Santa Fe Indian Market was kicking off in New Mexico, serious collectors were already stationed outside their favorite artists' booths in hopes of scoring a piece of their work.

Spanning two days, the annual outdoor market features hundreds of booths with the new works of more than one thousand Indigenous artisans from across North America; there's jewelry, textiles, fine art, pottery, and more. The annual event, now in its 102nd year, continues to be one of the city's most popular attractions, drawing an international crowd of serious collectors to Santa Fe (with their wallets in tow). This isn't your average market, after all: It features some of the most renowned contemporary Indigenous artists in the world, all of whom are carrying forward their cultural craftwork and traditions in new, innovative ways. By noon, many artists were completely sold out.

SANTA FE REPORTER | AUGUST 14 2024

Tony, Tony, Burning Bright

By Iris Fitzpatrick

It’s late summer in Santa Fe, and Downtown Subscription’s parking lot is jam-packed with expensive and beautiful foreign cars, opulent under an August sun whose light this morning bathes everything in a secretive pre-fall glow. I’m thinking about the way things look because I’m meeting with Tony Abeyta, whose angular landscapes are also lush; craggy hills softened by thick stripes of rain and dervishing blue-gray wind. Abeyta works in a range of media, but it’s these landscapes—rich with magpies, gods and forest fires—that launched him into art stardom.

Today, Abeyta says, he’s going for a “kinda gentrified” look with the fit: soft and spotless white tee, khaki shorts, white Adidas ankle socks and scuffed black Louis Vuitton loafers. He blushes when I tell him he’s a Santa Fe fashion icon, but he knows I mean it. Abeyta the sartorialist is one of his many moods. There’s also the son, the brother, the father, the fisherman; the flea-market-fiend and the Scorpio. Increasingly, Abeyta is known as art historian and expert appraiser, roles informed by a lifelong passion for collecting and trading beautiful things

NEW YORK TIMES | JULY 25 2024

Native Modern Art: From a Cardboard Box to the Met

By Holland Cotter

The Dakota Sioux artist who called herself Mary Sully is having an enchanting first survey at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but she came close to being swept off the stage of history. When she died in Omaha, Neb., in 1963, at age 67, her primary output of around 200 color-pencil-and-ink drawings lay hidden in a cardboard box kept by her older sister, with whom she had lived most of her adult life.

When that sister herself died a few years later, the box ended up among piles of ephemera waiting to be sorted through. Time passed. More than once the box came close to being tossed until one of Sully’s nieces, who happened to be a librarian, opened it and transferred the contents to a suitcase, which was then tucked away under a staircase.

More time passed. In 2006, the drawings resurfaced and came to the attention of Sully’s great-nephew, Philip J Deloria, who happened to be a history professor at Harvard, and who documented them in a terrific 2019 book called “Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract.” Last year the Met acquired much of the work. And now we have this rich, strange show, “Mary Sully: Native Modern.”

Mary Sully, Indian Church

HYPERALLERGIC | JULY 22 2024

Fritz Scholder’s Art of Non-Belonging

By John Yau

Being biracial in the United States means that you are the perpetual outsider. Fritz Scholder, who blasted apart the stereotypes of Native American people and life circulating in the mass media and tourist art, experienced the dilemma of non-belonging. Born in Breckenridge, Minnesota, in 1937, his ancestry was largely German, but his paternal grandmother was from the Luiseño tribe of California Mission Indians. Because of her, Scholder was an enrolled member of the federally recognized La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians.

While Scholder described himself as a “non-Indian Indian,” and vowed to never paint a Native American person, he broke that vow at different points in his career. His refusal to conform to expectations and his rejection of limiting definitions of his identity as Native American are high watermarks in postwar American painting. He both acknowledged his biracial identity and reminded us of the country’s legacy of eradicating Indigenous people and culture.

Fritz Scholder, Indian with Umbrella, 1972

HYPERALLERGIC | JULY 17 2024

Why Native Artists Are Reclaiming the Whirling Log

By Sháńdíín Brown and Zach Feuer

The Whirling Log symbol appears under different names and variations for communities across the world — manji in Buddhism, swastika in Hinduism. Specifically for the Diné or Navajo people, whose ancestral homelands are in what is now called Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico, the symbol is known by a variety of names in Diné bizaad (the Navajo language). It references the Diné Bahaneʼ or Navajo creation story and is generally understood as a harbinger of good luck, healing, and balance. But for some viewers dealing with historical trauma, it calls only one meaning to mind: Nazi propaganda.

Melissa Cody, Navajo Whirling Log, 2019

COWBOYS AND INDIANS | JULY 17 2024

Earl Biss: The Spirit Who Walks Among His People

By Chadd Scott

My favorite artist is Earl Biss. No. 2: Vincent van Gogh. When I say Earl Biss is my favorite artist, I’m not grading on a scale. I don’t mean my favorite painter or Native American artist; I mean my favorite artist.

I’ve felt a spiritual connection to Biss’ paintings, and him, from the moment I first saw his work. It’s unlike anything before or since. That first time was at The James Museum of Western and Wildlife Art in St. Petersburg, Florida, and I remember the moment as distinctly as I recall seeing my wife for the first time.

Lisa Gerstner’s documentary Earl Biss: The Spirit Who Walks Among His People, released in late April 2023, shares Biss’ genius and spirit and Gerstner’s personal background with Biss.

Earl Biss, Riders of the Foothills With a Witching Moon

ART NEWS | JULY 12 2024

Alex Janvier, Pioneer of Contemporary Indigenous Art in Canada, Has Died at 89

By Tessa Solomon

Alex Janvier, an Alberta-based painter and pivotal champion of contemporary Indigenous art in Canada, died on July 10. He was 89. The news was confirmed by his family on July 10 in an Instagram post. A moment of silence was held in his honor at the Assembly of First Nations annual general meeting that same day.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, writing on X, said: “His art reflected so much of Canada’s history, including some of the hardest parts of our story.”

In some of Janvier’s vibrant abstractions, lush forms contract and converge, suggesting the unfathomable natural world; in others, brisk lines and fierce swaths of red indict the historical mistreatment of First Nations.

“Painting says it all for me,” Janvier said in a statement in 2012. “It is the Redman talk in color, in North America’s language. Our Creator’s voice in color.”

Drawing Themselves Straight: The Son of Oregon’s Late Indigenous Artist Rick Bartow Begins to Walk in his Father’s Footsteps with a Gallery Show in Newport

EUGENE WEEKLY | JUNE 27 2024

By Bob Keefer

One night in late 2016, Booker Bartow — best known in those days, if at all, as a skateboard videographer and hip-hop DJ performing as “Nomadic” — was skateboarding down a hill near his home in the Nye Beach neighborhood of Newport when he hit a patch of black ice.

When he came to on the cold pavement, the 30-year-old had a fractured skull, a broken clavicle, a dislocated shoulder and several smashed ribs. He was bleeding from cuts and scrapes all over his body, but especially his head. No one came to his aid. He crawled back to his house and passed out again when he got inside, bleeding all over the couch. Before losing consciousness he took a selfie and posted it on Instagram, leading his uncle, who happened to see it, to come over and take him to the hospital.

That, Bartow says, was a pivotal moment in his life, which had lately been mired in a haze of alcohol, drug use and anger over the death that year of his father, the renowned Oregon artist Rick Bartow, and the death of his mother years before.

KOREAN JOONGANG DAILY | JUNE 24 2024

America revisited: Indigenous culture showcased in first Korean exhibition

In a scene from Bong Joon-ho’s Oscar-winning film “Parasite” (2019), lead actor Song Kang-ho wears a feathered headdress as he peers out from the bushes on a lawn decorated with tipis. This scene is an accurate representation of how Koreans visualize the Indigenous peoples of North America, who are still often referred to as "Indians."

It’s not that there isn’t a Korean translation for Indigenous Americans. Instead, there have rarely been opportunities in the country to straighten out the monumental mistake that Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) made centuries ago when he called Indigenous Americans "Indians," believing that he arrived in India. The National Museum of Korea aims to address this historical inaccuracy.

For the first time ever, there is an exhibition in Korea on the cultures and histories of Indigenous Americans at the National Museum of Korea in Yongsan District, central Seoul. Under the Korean title “Stories of the People Whom We Once Called Indians,” the exhibition addresses the historical inaccuracy of the terminology most commonly used in Korea.

The exhibition was co-organized by the Denver Art Museum and displays 151 selected items from its collection.

Fritz Scholder, Indian Power, 1972

ART IN AMERICA | JUNE 7 2024

Navajo Artist Melissa Cody Reclaims a Sacred Symbol That the Nazis Weaponized

By Alex Greenberger

In Melissa Cody’s 2014 weaving Good Luck, a figure known as Rainbow Man is represented as an electrical cord, his lower half culminating in a two-pronged plug. His tubular body encircles the phrase GOOD LUCK, and beneath those words, there’s a somewhat unexpected motif, formed from four right angles that meet at a central point.

Navajo viewers will understand the symbol as a whirling log, which connotes Good Luck’s titular well wishes. But to many other viewers, the symbol will likely read as a swastika. There are differences between the two symbols: a whirling log’s four angles form a square, whereas a swastika is rotated 45 degrees, creating a diamond. But those differences are subtle and easy to miss. That’s why it’s worth spending time with Cody’s whirling logs, which figure in two current New York solo shows, at MoMA PS1 and Garth Greenan Gallery.

Melissa Cody: Rainbow Road, 2023

THE TELEGRAPH | JUNE 4 2024

Native American artists edge ever closer to the million-dollar mark

By Colin Gleadell

At the major international Contemporary Art sales in New York last month, I thought I noticed a new trend. There were more Indigenous American artworks for sale than ever, and they were making record prices – a bright light in an otherwise fairly sombre marketplace.

Contemporary American Indigenous art used to be included in Native American sales along with the jewellery, blankets, totem poles and ethnographic tribal artefacts that remind us of bygone cultures. But with the call for change and diversity, the auction landscape shifted.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, I See Red: Talking to the Ancestors, 1994

BLACKBOOK | JUNE 4 2024

Cannupa Hanska Luger Honors His Indigenous Heritage with a New Public Sculpture

By Chloe Shaar

Tonight, the Public Art Fund will debut Cannupa Hanska Luger’s newest sculpture, Attrition. Made up of steel and ash black patina features, the 10-foot skeletal bison explores the relationship between animals, humans, and land in the context of Ingenious experiences within the United States. The opening reception will take place tonight, while the official viewing will be open to the public on Wednesday, which also falls on World Environment Day.

The sculpture will live on the pathway to City Hall Park in Lower Manhattan, the center of policy making within the city. The symbolism behind the sculpture confronts the past histories of the European settlers’ aggressive practices that took place in the 19th century, which inevitably led to the lack of survival within the bison population.

The artist behind the sculpture, Cannupa Hanska Luger, is a descendant of the buffalo people. Luger is an active member of the Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold and is Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara and Lakota. His ancestry and personal identity actively inspire the work he creates. Taking this into account while creating Attrition, the sculpture symbolizes Indigenous resilience and sovereignty.

APOLLO MAGAZINE | JUNE 3 2024

How Indigenous artists are holding their own in the art market

By Jane Morris

Does the Venice Biennale affect the art market? The consensus on this non-commercial festival, which opened last month, is usually yes. In the va-va-voom 2000s it was common to see collectors snapping up works by Venice stars as soon as they could at Art Basel (for years the Venice preview ended two days before the opening of the fair). ‘See in Venice, buy in Basel’ became an often-repeated phrase.

If the conventional wisdom holds true, this year should be a good one for Indigenous artists – those who trace their ancestries to the first inhabitants of countries such as Canada, Australia, Brazil and Norway. The winner of the Golden Lion for the best national pavilion, Archie Moore, is of Kamilaroi/Bigambul heritage. His stark, black and white installation in the Australian pavilion is a memorial to the 60,000-year history of his Aboriginal ancestors. Indigenous artists Jeffrey Gibson, Inuuteq Storch and Glicéria Tupinambá also represented the United States, Denmark and Brazil respectively.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, My Heart Belongs to Daddy, 1998

HYPERALLERGIC | MAY 30 2024

Shelley Niro on Her Life in Art

By Hyperallergic Staff

Shelley Niro (Kanien’kehaka) grew up watching her father craft faux tomahawks to sell to tourists who flocked to her birthplace, Niagara Falls. In this episode of the Hyperallergic podcast, she reflects on how witnessing him create these objects planted the seeds for her brilliant multidisciplinary art practice spanning film, sculpture, beading, and photography.

She joined us in our Brooklyn studio for an interview, where she reflected on growing up in the Six Nations of the Grand River, the Native artists she discovered on her dentist’s wall but rarely encountered in a museum before the mid-’90s, and her latest obsession with 500 million-year-old fossils.

Shelley Niro, Ancestors, 2012

HYPERALLERGIC | MAY 26 2024

Indigenous Artists Make Themselves Seen at the Thomas Cole Site

Comic by Steven Weinberg

Scott Manning Stevens, PhD Karoniaktatsie (Akwesasne Mohawk) curated the current show "Native Prospects" at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site. (Up through October 27th.) He has a word for depictions of Indigenous people in paintings like this.

The show he's organized at The Thomas Cole Site aims to shift the role of Indigenous people in American art from background decoration to the creators themselves. It's a brilliantly simple idea made all the more clear when you walk into the exhibition and see sculptor Truman T. Lowe's (Ho-Chunk) own waterfall made from strips of pine that referencing the splints used in traditional Ho-chunk baskets. It hangs right next to Cole’s waterfall.

FORBES | MAY 25 2024

A Native ‘Takeover’ At Baltimore Museum of Art

By Chadd Scott

“A Native takeover.” That’s how Dare Turner (Yurok Tribe), Curator of Indigenous Art at the Brooklyn Museum and former Baltimore Museum of Art Assistant Curator of Indigenous Art of the Americas, describes the Baltimore museum’s “Preoccupied: Indigenizing the Museum” initiative launched April 21, 2024.

“Preoccupied” includes nine solo and thematic exhibitions, a film series, a publication guided by Native methodologies, museum-wide education for staff related to Native American history and colonization, and a broad array of public programs through February 2025.

“It also includes audio tour stops where indigenous community members have gone into the galleries and selected any artwork they're interested in, which most of the time is not an artwork made by a Native person, and they speak about it from their perspective,” Turner told Forbes.com. “We also rewrote (wall) labels that had privileged white artists when they were depicting Native subjects. We flipped the script on that so the Native subjects were privileged.”

Julie Buffalohead, The Noble Savage, 2022

WHITEHOT MAGAZINE | MAY 21 2024

Beau Dick’s Dzunuk’wa Is Here for Your Soul

By John Drury

Here on the East Coast and in New York City, we are about as far as one gets from artist Beau Dick’s beloved home of choice, Alert Bay. He who was Walas Gwa’yam by name - the “big, great whale” - and a Hereditary Chief of his people, even now posthumously, continues to expand his philosophical reach by way inarguable artistic talent and the shared tales of his indigenous people. Beau’s warnings of the inherent and matched evils of colonialism and capitalism come to us from the woods, deep in the ancient and old-growth, wooded forests of the Pacific Northwest and are timeless, as revealed in the reflection today’s ongoing and evil land grabs and rampant greed, fueled of war and division.

Beau Dick, Wind, 2005

FINANCIAL TIMES | MAY 10 2024

Wendy Red Star: ‘Native artists are hot right now’

By Joshua Hunt

When I visited Wendy Red Star at her studio in south-east Portland, she described her work as that of a “visionary” rather than an artist. “I don’t think I’m an artist, at least not in the western sense,” she said. “I’ve never tailored my stuff to fit in the art world.”

The products of her vision were scattered all around us, illuminated by the late-morning sun: sculpture, mixed-media installations and many, many photographs of Native Americans. Some of these were archival images of long-dead ancestors that she had annotated and embellished with red pen, others surrealist self-portraits that seem to cast the artist as the star of Technicolor melodramas satirising white views of Native American life in the 19th and 20th centuries. In “Fall”, for example, from her 2006 self-portrait series Four Seasons, Red Star sits alongside an inflatable deer in front of a painted backdrop, dressed in the ornate regalia of the Crow people, a Native tribe indigenous to America’s northern plains. All around her are plastic flowers and leaves that evoke the artificiality of indigenous life as dramatised by natural history museum dioramas.

Wendy Red Star, Her Dreams Are True (Julia Bad Boy), 2021

EDGE EFFECTS | MAY 2 2024

How Indigenous Artist George Morrison Resists Ecological and Cultural Extraction

By Matt Hooley

In 1965, George Morrison started making landscapes out of driftwood. He gathered wood from Atlantic beaches near Provincetown, Massachusetts, where he rented a studio on breaks from teaching at the Rhode Island School of Design. He looked for scraps of wood grayed and weathered by the sea to the brink of abstraction, but that also bore some trace of human use or attachment. Morrison began each landscape, which he also called “wood collages” and “paintings in wood,” by fitting together a few pieces in the bottom left corner of the frame that, along the broken lines of driftwood edges, gathered out into massive sweeps and rivulets of fragments to fill frames up to fourteen feet wide and five feet tall. Setting off the top quadrant of each collage, a single, twisted but unbroken line—a horizon line—is the only gesture spared from the turbulence of fracture and motion that characterizes the landscapes.

George Morrison, Red Cube, 1983

‘It is a conversation you’re having with your loom’: Melissa Cody on her lifelong relationship with weaving

THE ART NEWSPAPER | MAY 2 2024

By Wallace Ludel

Webbed Skies at MoMA PS1 is the first major museum exhibition for Melissa Cody. Cody is a fourth-generation Navajo/Diné weaver, and much of her practice is rooted in the Germantown Revival style: a type of Navajo weaving developed when weavers began to take apart the commercially dyed blankets provided to them by the US government, repurposing the fibres to create tapestries rooted in their own traditions. This style is also indicative of Cody’s work in its harmonious blend of generational practices. While her work is no doubt an offspring of ancestral tradition, it is also a bridge towards a new generation of weavers and artists, as well as towards a large, international audience.

NEW YORK TIMES | APRIL 26 2024

Baskets Holding the Identity of an Indigenous People

By Hilarie Sheets

Long before painters such as Winslow Homer and Andrew Wyeth arrived in Maine to capture its spectacular natural beauty on canvas, the native Wabanaki people used materials from the landscape to weave black ash and sweet grass baskets, the oldest continuously practiced art form in the state.

“It’s said that our cultural hero, Glooskap, fired an arrow into the black ash tree and our people came dancing out — it’s tied to us,” said Jeremy Frey, a 45-year-old, seventh-generation basket maker from the Passamaquoddy tribe, one of several in the Wabanaki Confederacy.

Frey’s vibrant and innovative baskets — remarkably contemporary forms woven with ancestral knowledge — have caught the attention of the art world and put him at the forefront of a wave of interest from museums, galleries and collectors in the work of Native artists. (This month, Jeffrey Gibson is the first Indigenous artist to have a solo exhibition in the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.)

Jeremy Frey, Nostalgia, 2022

THE ART NEWSPAPER | APRIL 19 2024

The legacy and mystery of the display of Native American art at the 1932 Venice Biennale

By Claire Voon

In December 1931, the Italian commissioner of the 18th Venice Biennale penned a plea to organisers of the United States pavilion, who had yet to fully deliver their vision for the impending international art exhibition. “We should like some of your very great artists like Whistler,” he wrote, “and as for the living ones we should allow a room for [Paul] Manship as Sculptor, and [Maurice Sterne], or some others, as painters.”

The following January—four months before the exhibition’s opening—a reply arrived from New York. It confirmed that the US pavilion would feature, out of four rooms, one devoted to art by Native Americans, among them the Pueblo painters Fred Kabotie and Awa Tsireh. It would include neither Whistlers, nor Homers, nor Sargents—conspicuously setting aside the era’s assumed “great artists” to shine an international spotlight on lesser-known Indigenous names.

The resulting display was historic: it marked the first time that Native American artists represented the United States at the prestigious art exhibition, a distinction that has repeated only this month, with the Chocktow Cherokee artist Jeffrey Gibson’s takeover of the US pavilion at the 60th edition of the Biennale (until 24 November). Yet it has largely been forgotten, according to Jessica L. Horton, a professor of modern and contemporary Native American art at the University of Delaware.

NEW YORK TIMES | APRIL 18 2024

A Millennial Weaver Carries a Centuries-Old Craft Forward

By Patricia Leigh Brown

Spiders are weavers. The Navajo artist and weaver Melissa Cody knows this palpably. As she sits cross-legged on sheepskins at her loom, on one of the wooden platforms that boost her higher as her stack of monumental tapestries grows, the sacred knowledge of Spider Woman and Spider Man, who brought the gift of looms and weaving to the Diné, or Navajo, is right there in her studio with her.

It also infuses “Melissa Cody: Webbed Skies,” the first major solo exhibition of the artist’s work, which is on view at MoMA PS1 through Sept. 9. in a co-production with the São Paulo Museum of Art in Brazil (known as MASP).

Detail of “Power Up” (2023)

At the Venice Biennale’s Contemporary Showcase, Living Artists Examine Queer and Indigenous Legacies

ARTNEWS | APRIL 17 2024

By Maximilíano Durón

As the international art world has descended on La Serenissima this week, the 2024 Venice Biennale began the first of its preview days on Tuesday morning, with visitors heading to either (or both) of its main venues: the Arsenale and the Giardini. Curated this year by Adriano Pedrosa, the closely watched artistic director of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo, the exhibition, titled “Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere,” focuses on Indigenous artists and artist from the Global South, highlighting the vastness of art that is out in the world today and, with the historical section, throughout the 20th century.

Emmi Whitehorse, Typography of Standing Ruins #3, 2024

ART BASEL | APRIL 15 2024

For these Native American creatives, fashion and art are inextricably linked

By Stephanie Sporn

Tradition versus innovation. Authenticity versus stereotype. Pride versus pain. To be a Native artist in today’s contemporary landscape is to constantly juggle centuries-old tensions, frequently echoed within the history of one’s chosen artistic medium. ‘The visual aesthetics of Indigenous communities are innately tied to alternative media that have often fallen into the category of “craft,”’ says John P. Lukavic, Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Native Arts at the Denver Art Museum, one of the first American institutions to collect Indigenous arts.

For centuries, ‘Indigenous people have expressed many aspects of themselves through regalia, beadwork, embroidery patterns, animal skins, and feathers that also express family ties or clans, life accomplishments and spiritual beliefs,’ says Kent Monkman, a Canadian First Nations artist of Cree ancestry. The interdisciplinarian is known for his charged paintings critiquing colonization, as well as his performances as his gender-fluid alter-ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. ‘Art was not separate from other aspects of life, so creativity was and still is expressed through clothing and the creation of ceremonial and everyday objects.’

Kent Monkman, The Great Mystery, 2023

SAN DIEGO UNION-TRIBUNE | APRIL 14 2024

Her large-scale photos speak thousands of words about Indigenous communities, identities

By Lisa Deaderick

Contemporary fine art photographer Cara Romero is thoughtful and deliberate in her work and particularly in her selection of photographs for her solo exhibition this month at the Museum of Photographic Arts at the San Diego Museum of Art in Balboa Park.

“The Artist Speaks: Cara Romero” is divided into three sections: Native California, Imagining Indigenous Futures, and Native Woman, and there’s a clear purpose to offer representations of her culture, history, and lived experience from her perspective as a Native American woman.

Cara Romero, 3 Sisters, 2022.

NEW YORK TIMES | APRIL 13 2024

Representing the U.S. and Critiquing It in a Psychedelic Rainbow

By Jillian Steinhauer

People in Venice might hear the jingle dress dancers before they see them. On April 18, some 26 intertribal Native American dancers and singers from Oklahoma and Colorado will make their way through the winding streets and canals of the Italian city. Wearing brightly colored shawls, beaded yokes and dresses decorated with the metal cones that give the dance its distinctive cshh cshh rattling sound, they’ll make their way to the Giardini, one of the primary sites of the Venice Biennale. There, they’ll climb atop and surround a large red sculpture composed of pedestals of different heights and perform.

The jingle dress dance, which originated with the Ojibwe people of North America in the early 20th century, typically takes place at powwows. In Venice, it will inaugurate the exhibition in the United States Pavilion on April 20. Titled “the space in which to place me,” the show is a mini-survey of the rapturous art of the queer Choctaw and Cherokee artist Jeffrey Gibson.

MVSKOKE MEDIA | APRIL 12 2024

Ofuskie projects his passion for painting and Indigenous people through acrylics

By Braden Harper

Artist George Alexander (Mvskoke) has come a long way from growing up on the Mvskoke Reservation in Mason. Alexander goes by the name Ofuskie, an homage to Okfuskee, the county he grew up in. Although Alexander has been making art his entire life, his hard work and dedication has culminated into owning his own art studio where he produces original paintings. Alexander was named as one of this year’s National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development’s 40 under 40 honorees for contributions to his community.

George Alexander, What’s That Over There?

HYPERALLERGIC | APRIL 10 2024

Rose B. Simpson’s Soaring Metal Sentinels Watch Over Madison Square Park

By Elaine Velie

Santa Clara Pueblo artist Rose B. Simpson’s first New York City solo public artwork has arrived in Manhattan. Seven 18-foot-tall figures surround a bronze female form in Seed, on view in Madison Square Park through September 22. The installation’s weathered steel sentinels are the artist’s tallest sculptures yet.

“They transform the nature of a hectic and scary city, in a sense, to a place that’s really safe,” Simpson said at the work’s unveiling today, April 10. She explained that they mimic the energy of the park, a place people go to reconnect with their humanity. “They become these protectors of what they’re looking out for, so that [the inner sculpture] can close her eyes. So she doesn’t have to be worried or on.”

ART BASEL | APRIL 9 2024

The transformative rise of Indigenous and First Nations artists

By Stephanie Bailey

At the Venice and Sydney Biennales, they highlight the importance of stories and perspectives rooted in land and sea.

The wave of Indigenous and First Nations artists exhibiting in national pavilions for the first time is undoubtedly the Venice Biennale’s most significant development in recent years. In 2019, the Isuma collective became the first Inuit artists to occupy the Canadian Pavilion, with Zacharias Kunuk’s film, One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2019), recounting the forced relocation of Inuit people in Canada. Then the Nordic Pavilion transformed into ‘The Sámi Pavilion’ in 2022, with artists Pauliina Feodoroff, Máret Ánne Sara, and Anders Sunna illuminating an Indigenous community stretching from Norway to Russia, as Yuki Kihara became the first Pacific, Asian, and fa’afafine artist to represent Aotearoa New Zealand.

Eric-Paul Riege and his installation at the Sydney Biennale

ART IN AMERICA | APRIL 9 2024

Kay WalkingStick’s Layered Landscapes Get Under the Genre’s Surfaces

By Alex Greenberger